Car of the Week: 1948 Chrysler Windsor Club Coupe Street Rod

He didn’t want the ’48 Chrysler project, but he built it any way!

By Larry Jett

In early 2007, I received a phone call from the owner of a transmission shop. We were not acquainted, but he had heard that I was conversant in things MoPar. Turns out that he had owned a stalled street rod project based on a 1948 Chrysler Windsor club coupe. My response was that I had restored a dozen Chrysler products over the years, but had little interest in street rods. As the president of the California Chrysler Products Club, progenitor of the W.P. Chrysler Club, I promised to bring the subject up at the next regular meeting. I also asked the price of the project. “No price, I just want it gone,” said the tranny shop owner. At the meeting, interest in the project was even lower than its quoted price and I soon forgot about the call.

Weeks later, as I drove down my driveway, I came upon a completely dismantled car body on the tanbark with boxes and bundles and bags of small parts plus hundreds of bolts and nuts in cans. All of the parts were stuffed into the orifices of the primered and stripped car body on wheels with nothing attached. The doors, fenders, trunk and hood were all removed; there was no instrument panel or seats or upholstery of any sort. Somewhat irate, I called the shop owner who explained that a young man who hangs around his shop heard him talk about the project car, and since my wife had been his high school teacher, he said he would load up the shop’s flatbed and deliver the car to my house. We agreed that if I didn’t find a home for the project car, the shop would retrieve it in two weeks.

Assessing the “coupus delicti,” I found a 9-inch Ford rear end, disc rotors and calipers on the front, a junky and rusted big-block V-8, motor mounts and a properly prepped coupe body. However, there was no transmission or drive shaft, nor a cross member to support a TorqueFlite. Not a single avenue toward finding a donor owner worked out and I began preparing to have it reclaimed when I had a restless night. That night, I started thinking (which can be dangerous at 2 a.m.), would the coupe look great in a dark-blue metallic color? What about woolen Highlander plaid seats, only in Black Watch green and blue trimmed in blue leather? Maybe chromed reversed wheels with the 1948 hubcap centers as I had coveted in the ’50s, but could not afford as a teenager? All these thoughts were dismissed because few would understand a street rod on a Chrysler body, and as sleep was softening my brain, the last “what if’ whispered: “How about a Chrysler Town and Country tribute?” Almost everybody in the old-car hobby could comprehend that. The muses of the “Oh-dark-thirty” had spoken; I would start tomorrow by ordering a subscription to Street Rodder magazine.

The pieces come together

My brother-in-law was talented in wood work and he agreed to form the ash surroundings of the wood-grained wallpaper, so I gave him $1000 to buy wood. I never got so much as a matchstick produced, but these things happen, don’t they? I also considered that some company might have made fake wood kits, such as Chevrolet buyers had available in the middle 1940s, or perhaps a vinyl wrap could be purchased that replicated the wood sides and trunk. The actual companies that create wood for genuine Town and Country woodies wanted a half year of my salary and wanted this “Left Coast” car to be shipped to East Coast places. That was not to happen. The determination to make a faux woodie dissolved at the end of the first year of construction — then other challenges arose.

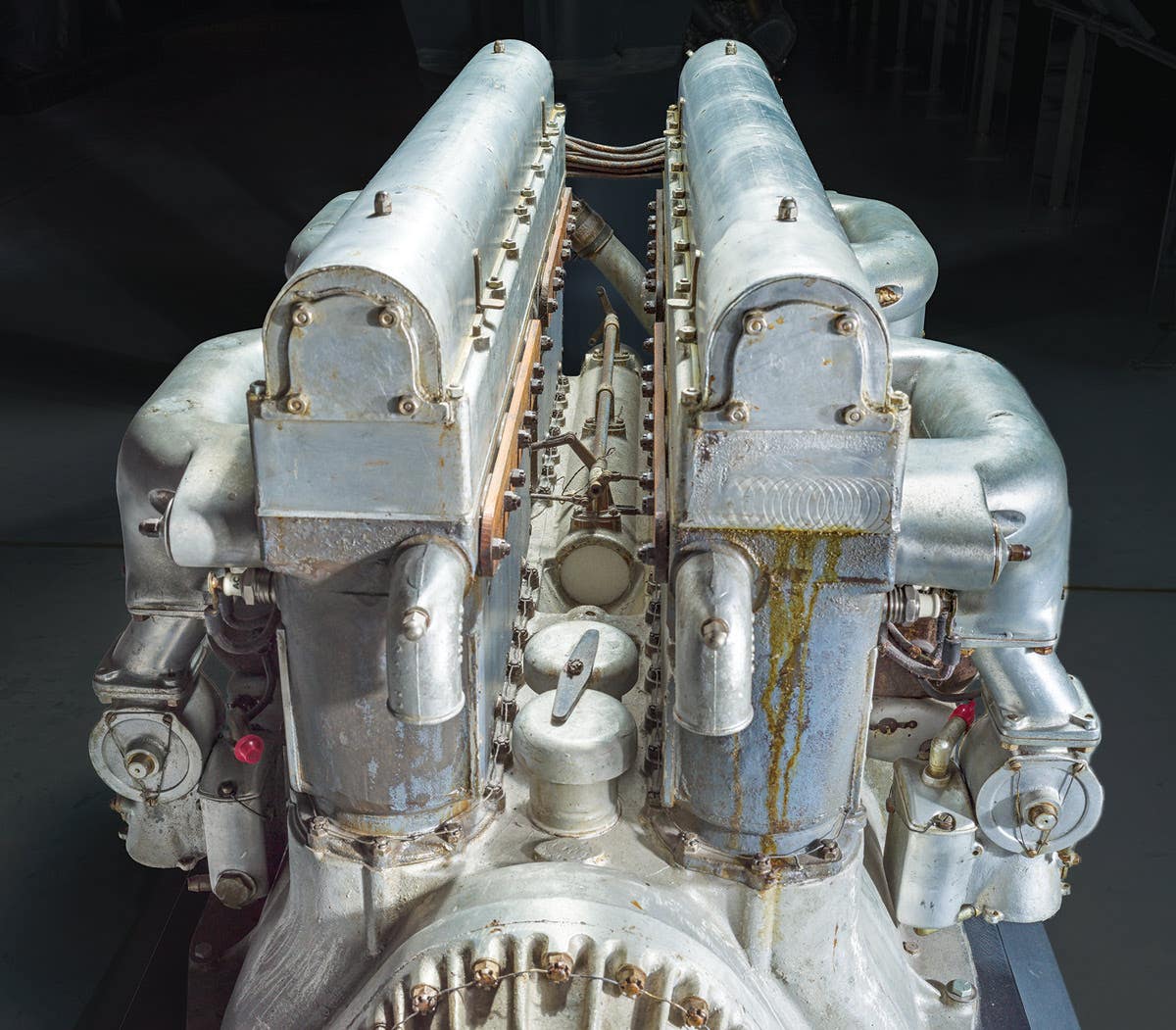

Many folks doubted I had the skill set to make something out of the quagmire of metal puzzle pieces, and that included me. A drivetrain needed to be sourced and it had to be cheap. Popular wisdom pointed to a 350-cube Chevrolet V-8, but no mouse motor would be attached by this MoPar nut. Months later, a neighbor who was a real estate agent told me that he had an estate sale listing that required the garage to be emptied and included was a 1966 Chrysler New Yorker. I looked the car over and to my delight I found that almost every body panel had rubbed up against something during drinking hours, but the engine had new gaskets showing its “go” parts had been well maintained. For $350, I bought a car that provided a 440-cid V-8, TorqueFlite, driveshaft, cross member for the automatic transmission, radiator, power brake booster and master cylinder. A power wash of the engine and some Chrysler turquoise engine paint and to my amazement, I found that it fit well in the space designed for a flat-six; I didn’t even have to remove the inner fender skirting that kept out road dirt. The 1966 radiator was easily adapted to the space behind the grille, and there was room for the stock fan to live. I cut the driveshaft to length and had a Ford yoke end welded at the rear and the drivetrain was complete. It was then that I ascertained that the body was not bolted anywhere to the frame. Only gravity kept the two major components connected when the car was loaded and unloaded during its past transfers. This discovery showed that a donor parts car would be more helpful than just acquiring an instrument panel and seats. There was much to be learned about how the coupe was first built when addressing the meatless skeleton I now owned.

Searches on eBay located a very worn $600 Windsor sedan in Hollywood complete with the Highlander option. Not knowing any better, I hitched up my tow dolly to the back of my wife’s Toyota Highlander (without any trailering specs) and drove to Hollywood from the San Francisco Bay Area to drag home the sedan. Now I could remove chassis-to-body bolts and bits from the donor, clean and chase threads and insert them where appropriate into the coupe.

Employing imagination and ingenuity

Then the question of controlling the TorqueFlite bubbled up. A floor shifter would be easy, but I planned on using the bench seats from the donor, making floor shifting look unnatural. About then the rod magazine told of a product under development by Moon Equipment Co. (Mooneyes). A long telephone chat taught me that there would be a rectangular box with pushbuttons that electrically excited a small computer that actuated a solenoid forward or backward to shift the tranny bands. “I want one, how much and how soon?” I asked. Moon wasn’t ready to take orders, but I’ve made a career in auto sales and leasing so I was able to outsell them and got a promise to get the first one if I sent $900 today.

There was plenty of other work to do in the meantime, but after nine months without contact from Moon, I called to complain only to learn that Moon had decided not to go forward because of liability concerns of a major component made in Europe. Two of the Moon employees had left the company to continue further development work and I was able to get a phone number. The principal of the new concern promised to send me what was possibly a prototype, because I have never heard of another electric shifter for any make automatic transmission. It turned out to perform as promised and fit nicely into the dash where the factory radio once resided. It also mimicked the factory clock on the other side of the radio speaker enclosure. After installing a hidden 500-watt Alpine/Sony sound system, I used the abandoned radio speaker home site as the major air conditioning outlet. Once I installed the air conditioning, power windows and locks and the stereo, I finished the paint and seats and wiring and the wheels. I considered power steering was for sissies. Wrong! It became apparent that if I drove down an alley and there was no exit, I would have to abandon the car.

Gig employment is available at the Home Depot parking lot, so I hired three guys to help me lift off the nicely painted front clip while I waited for Fat Man Fabrications to send me a rack-and-pinion setup plus a power steering pump and pulleys to ease the angst of steering. Four years after I completed it, I took it to a national Chrysler 300 Club meet I hosted in Carmel, Calif., where a buyer surfaced. He intended to drive it to Portland, Ore., which was a worry to me, because much of the making of the car was unorthodox. However, it made it there without trouble and is still there as far as I know.

I will never do another car, but the satisfaction of finding a way around a vexing problem using only imagination and ingenuity is good medicine for an aging brain.

*As an Amazon Associate, Old Cars earns from qualifying purchases.