Austie’s ‘Silent’ Auction

Ground-breaking, unpublicized sale was for early hobby purists only.

The 1899 Oakman-Hertel runabout was a favorite among the

cars at the Long Island Museum. Even so, Henry Austin Clark,

Jr., put it in his first auction in 1963.

“After 15 years of operation of the Long Island Automotive Museum, it has become obvious that the displaying of cars to the public is a losing proposition,” said Henry Austin Clark, Jr. “Therefore, it is planned to discontinue operation of the museum after the 1963 season, unless some sort of miracle occurs.”

At the time of this proclamation, the old car hobby was emerging from its infancy and was maturing. The interest level of the general public was admirable and growing, but not at a rate to sustain a variety of visionary car museums spotted throughout America and Canada. Located on Route 27 in Southampton, N.Y., Clark’s operation seemed poised for success. At least, that was his dream.

But the museum needed to meet its bills. In Clark’s case, it was a battle he was no longer willing to wage.

“Austie,” as he liked to be called by friends, had tremendous ability to find and obtain rare cars, and also gather rare documents from car companies, which he honored along with piles of literature that he purchased piece by piece or in bunches. But in 1963, he had had enough of the museum business.

“A group of favorite cars will be retained as a private collection,” Clark announced. “This sale [set for June 22, 1963] is one of the first steps in reducing the collection to modest proportions.”

It was an auction that attracted collectors with a broad spectrum of interests to the museum. They respectfully kicked tires. They fondled brass, nickel and chrome trim. They peered into cavernous engine compartments andwhiffed the ancient leather-and-wool provenance of rare vehicles.

Earlier, the first significant early auction of vintage cars caught the attention of collectors, including Clark. That was the John C. Sword sale held in the fall of 1962. The event was staged in Ayershire, Scotland. In all, 119 vehicles were involved, generally ranging in age up to 1930. Participants claimed bidding hysteria drove prices upward.

Clark also knew about another auction held on Long Island. In fact, he was among the bidders. It was the collection of Wallace C. Bird. The estate was settled in May 1962. A bullhorn was used for the outdoor event held adjacent to the garage complex that housed the cars. High-dollar bids even foiled representatives of William Harrah, who eventually amassed his own huge and valuable collection.

Not much was reported about the Long Island event. That’s the way Clark wanted it. “No information regarding names of buyers will be made public, and all publications are requested not to assign writers or photographers to cover,” he said. He gave no reasons in print, but it was known that he was totally against the hysteria of the Bird auction. Siding with the hobbyists, Clark was part of a movement in the old car hobby that preferred conservatism, not flamboyancy.

The lack of news coverage also helped avoid taxes. Clark clearly stated that “buyers will be furnished a bill of sale and a New York State Dealer’s Certificate of Sale (Form MV-50).” Quite clearly, those were the days when the hobby was far from any aspect of big business and multi-million-dollar bids.

It is hard to obtain information about such a shrouded event, especially after more than 45 years. But a modest bit of behind-the-scenes documentation exists.

Following are some of the results from that landmark sale, now put to print long after the dust has settled and most of the buyers (plus the seller) have passed from this life. However, out of respect to Austie Clark, names of buyers will still be withheld.

n One successful bidder took the gavel at $2,500 for the 1899 Oakman-Hertel runabout. This two-cylinder, 2 1/2-hp vehicle operated on pulley drive. Said Clark, “The basic plan of this little car was derived from two bicycle frames with the rest of the car in between. This fine example of one of America’s earliest machines was found in a garage in Lynn, Mass., years ago by John Leathers who purchased it for D. Cameron Peck. Cameron had the leather, solid rubber, and coachwork restored. Mechanically, it has never been touched.”

The car brought spirited bidding. It was listed first among the cars, more due to age than anything else. In 1963, there was an extremely keen interest in brass-era horseless carriages. A Hertel, most likely a sole survivor of the brand, was something to be cherished by those who enjoyed the rare and unique. Early bidding probably hastened its rise in price. Since auctions of this magnitude were rare, bidders seemed more aggressive. No one knew if and when the next auction might take place anywhere in the land.

As the seller indicated, there was no set pattern on how to construct a car in 1899. It was purely a matter of the builder’s preference and what would succeed through trial and error. Also known as the Hertel, the vehicle had sold new for $750 and was a step above some of the crude vehicles made at that time. The genesis of the Hertel stretched back to 1895. By 1900, the Oakman Motor Vehicle Co. of Greenfield, Mass., was in trouble and manufacturing soon ceased.

Peck was a powerhouse among car collectors, amassing a considerable amount of cars, literature and notoriety among fellow hobbyists. Thus, the Hertel had “pedigree.”

In an age when late, pristine Classics were selling for $1,000, a shade more was paid for horseless carriages. The bid of $2,500 was quite an amount. In effect, it was the price of a new car.

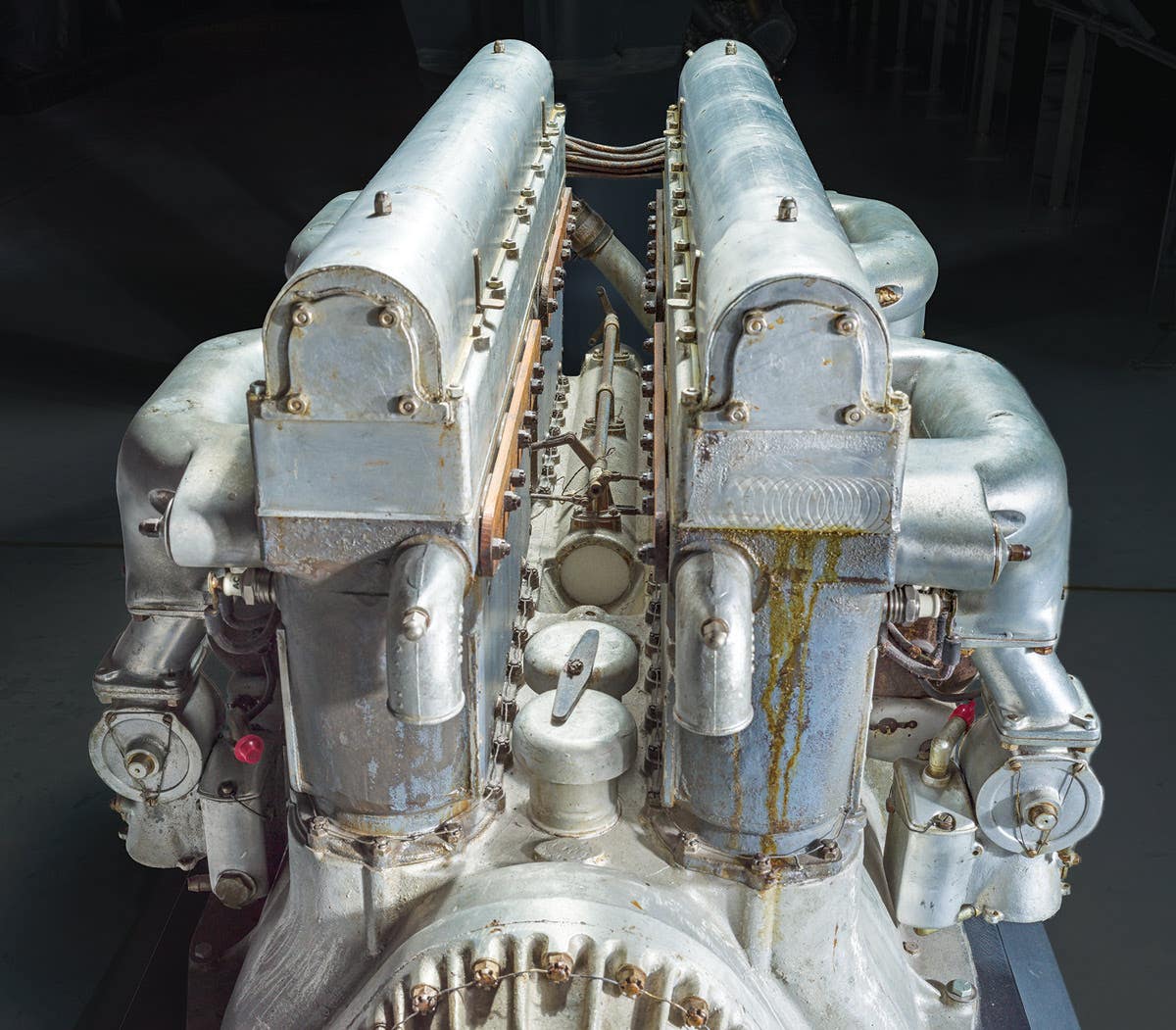

The same bidders went after Clark’s 1904 Franklin with rear-entrance tonneau, a Model B, four-cylinder, 10-hp car. The air-cooled engine was positioned crossways in front to equalize cooling. Clark had the paint and leather restored by a man named Reuter, with mechanical work being completed by a Mr. McKeage. “We never finished hooking up the ignition system and have not run it since restoration,” Clark noted. Even so, it sold for $2,050.

The same bidder had his eye on at least two more cars in the collection: A 1914 Chevrolet Amesburty Special roadster and a 1914 Pierce-Arrow seven-passenger touring.

Bidding advanced on the Chevrolet. It went in spurts. Some buyers reasoned it was “just a Chevy,” not quite the equal to a luxury car in bid price. Others theorized that the car was worthy of a high bid due to the popularity of the Chevrolet name and its legendary history prior to folding into General Motors. So the offers ran higher and higher.

“This is one of the large early Chevys much different from the little cars of the ’20s,” Clark noted. “Goes like a bomb and has wire wheels with 34-by-4-1/2 tires. Lots of class with no top, but instead a dust shield.” What helped boost the price was prior ownership by George Crittenden, well known as a Boston collector. He ran the car at early meets and even the Glidden tours of the late 1940s. Austie admitted that the paint wasn’t perfect, but it “is not too bad.” The final bid was $2,000, and came from the new owner of the Hertel.

Heretofore, there were few experts on what became the fine art of vintage car auctioning. Certainly, a few old cars were being offered occasionally at auction venues, but most of those events were staged by local companies that handled all types of items from entire households to expensive jewelry. Now, a “new breed” of auctioneer was maturing alongside the old car hobby.

As for the Pierce, we’ll examine its fate in Part 2.

[Editor's Note: Part 2 will be published in an upcoming issue of Old Cars Weekly. For subscription information CLICK HERE]