The 1940 Ford Turns 70

Yup, it’s been seven decades since the iconic 1940 Ford hit the streets, but who’s really counting?

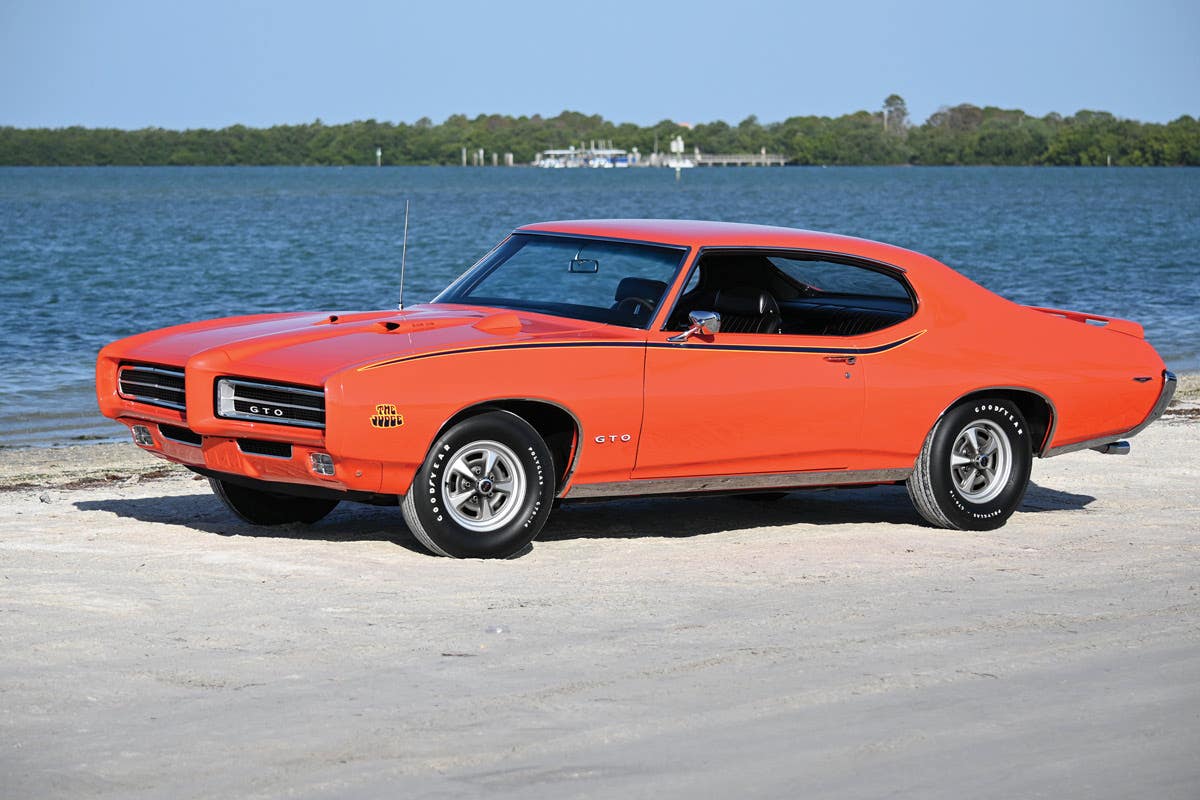

Downhill all the way and the scourge of Lynn, Mass., Paul

Bourque’s green ’40 coupe was waaaayyyy down in front, and

he’d installed a Model A spring in back to raise the rear and give

it a righteous tilt. Under the hood (although the hood was often

not used), was a 371-cid Olds V-8 with factory Tri-Power.

(Ken Gross photo)

If you read this column regularly, you know I’m a devoted fan (you could say fanatic) of Ford’s ’40 DeLuxe business coupe. Although FoMoCo’s late-’30s coupes, the ’38s and especially the ’39s, combine a distinctly pointed, nautically influenced prow with that beautifully sweeping, S-curved rear profile, Ford’s design boss, E.T. “Bob” Gregorie, really nailed it with the ’40 DeLuxe. Then and now, it’s beautiful from any angle.

Reportedly, Gregorie had been frustrated with Ford’s then-standard 112-inch wheelbase. He wanted a much longer car, more like the gracious Lincoln-Zephyr (which he also designed). In 1934, he’d cleverly devised a way to extend the standard Ford’s wheelbase some 10 inches. The spring and crossmember remained in their original location, but with special brackets, the axle was moved forward. He even had a demo chassis fabricated to prove it could be done, but Ford chief engineer Lawrence Sheldrake would have no part of a suspension design that had been dreamt up by the head of Ford styling. Gregorie’s idea found its way onto a special one-off roadster, in late 1934, that was built for Edsel Ford, but as far as a production design was concerned, the notion was quickly scrapped.

Thanks to a 4-1/2-inch custom crank and a

3-7/16-inch bore, Whitey Tower’s impressive-

looking, four-carb, Weiand-equipped,

flathead displaced 334 cubes. Tower’s car had

a gorgeous tuck-and-roll Naugahyde interior,

and the garnish moldings were plated. Has it

survived? I wish I knew.

Bill Commane’s coupe ran a ’37 Cad floorshift

and he’d updated the brakes with Lincoln

Bendix drums. Commane looked to be in his

50s. It featured a chromed ’39 Ford-style

windshield frame, and twin side exhausts

exiting on the left. I’d love to find that car,

wouldn’t you?

So Gregorie just extended the ’40’s hood even further past the front fenders. That styling trick reached a peak with the ’40, because for ’41, Ford engineers provided a two-inch longer, 114-inch wheelbase. But back to the ’40: when you look at a side elevation, you can actually see that hood extension, and the effect works quite well. Unlike the curvaceous Lincoln-Zephyr coupe, which only came in a smart-looking, exclusive three-window configuration, the ’40 was a five-window, as had been every Ford coupe since ’37.

In keeping with previous practice, the Vee-ed ’39 DeLuxe front end design morphed into the ’40 Standard, and the slightly more expensive ’40 DeLuxe front end was all new. Out in California, an eager LA hot rodder, Earl Bruce, bought a nearly new ’40, chopped the top and filled the rear quarter windows. Bruce is in his 80s and he still owns that car! And in 1942, the Brand Brothers body shop chopped and channeled a ’40 coupe for Bob Creasman. They fabricated full-length fadeaway fenders, anticipating Jaguar’s XK120 coupe in 1949. That car survives, as well, and it appeared at Pebble Beach a few years ago.

For the most part, especially back East, ’40 Ford coupes were seldom chopped. Not only were those sleek compound roof curves a forbidding challenge, but many people (myself included) felt the stock roofline on a ’40 looked just fine. Lowering a ’40 was easy – you’d just install a dropped axle in front, reverse the spring eyes, flatten the spring, and you were there. In back, a few enterprising rodders actually zee-ed the frame, but most guys — before hot rodders began installing 9-inch Ford rears and parallel leaf springs — either altered the rear cross member or simply torched the spring (not a good idea, but hey, it was the ’50s!) and added six-inch shackles. An anti-roll bar helped with side sway, but these modifications were never about improving a car’s handling, they were about looking cool.

The ’40 had hydraulic brakes, of course, and the ’39’s ungainly “wide 5” wheels were replaced by a new variation with a standard 5 x 5-1/2-inch bolt pattern, so a variety of large and small hubcaps could be fitted. If you didn’t use a plain, full-sized accessory cap, you may have opted for baldies (’40 caps without the script) or later ’46-’48 “dog dish” caps. By the late ’50s, customizers switched to later Mercury 15-inch wheels and their handsome flat caps, often chroming and even reversing them.

When I was in high school, the owners of my two favorite coupes took very different approaches toward getting a ’40 down into the weeds. A guy named John Knowles owned a stylish primered tail dragger, with a dramatically lowered rear and a barely lowered (if it was at all) front. Knowles used those wonderful period single spinner bar caps on red-painted steelies, and they flickered beautifully in the sun when the car was underway. (That flipper bar design first appeared on late-’30s Cadillac V-16s, and accessory companies quickly copied it).

He’d also fitted ’38 De Soto ribbed bumpers, Foxcraft steel fender skirts and he’d dechromed the hood and the decklid. The flathead was mildly modified, and Knowles often drove without the hood to show off the classy 59A block with its chromed and red-painted accessories. His car epitomized custom cool as far as I was concerned. Although we wouldn’t have used the term back then, it was definitely a “chick magnet.”

Over in the next town, Paul Bourque’s dark green ’40 coupe was just the opposite. It was waaaayyyy down in front, and he’d installed a Model A spring in back to raise the rear and give it a righteous tilt. Under the hood (although the hood was often not used), was a 371-cid Olds V-8, I think, with factory Tri-Power. He’d removed the caps for that racy look. The rubber was 15-inch, with 5.60’s and 8.20’s. From memory, I’m pretty sure he ran a sturdy LaSalle three-speed adapted to the Ford torque tube. Paul ran his car at the drags at Sanford, Maine, and I believe it turned speeds in the high 90s.

My own ’40 coupe was acquired in a trade for a custom ’50 Chevy. I began the installation of a 303-cid ’50 Olds, backed by a ’39 top-loader, then traded the unfinished project for a cherry, jet-black ’48 club coupe, which I proceeded to modify extensively. Several friends owned ’40 coupes. I wanted one in the worst way. So I never stopped collecting clippings of ’40 coupes I liked, in the “little books” and in Hot Rod Magazine.

Bob Brown of Pico, Calif., had a flamed, louvered and raked ’40 with a big 304-cid stroker flattie. A Rod & Custom feature car in February 1954, it absolutely defined the look for ’40 Fords But my very favorite was Whitey Tower’s ’40 with a massive flathead. Thanks to a stretched 4 1/2-inch custom crank and a 3 7/16-inch bore, Tower’s impressive-looking, four-carb, Weiand-equipped flathead displaced a then-whopping 334 cid. Years later, I tried calling Glendale, Calif., information looking for a Dwight Tower (Whitey was a popular ’50s nickname for guys named Dwight), but never found him. Tower’s car had a gorgeous white-and-yellow, tuck-and-roll Naugahyde interior, and the garnish moldings were plated. I’ve long wondered if it survived, or was junked, or whether it’s moldering away in an old garage somewhere, awaiting discovery.

Another ’40 that always fascinated me was Bill Commane’s GMC-powered coupe, from Van Nuys. Today, we think nothing of Chevy V-8 installations in Fords, but decades ago, stuffing a big 332-inch bored-out, Manny Ayulo-built “Jimmy” into a Ford was very unusual. The trans was a ’37 Cad floorshift and he’d updated the brakes with Lincoln Bendix drums. I was able to turn up a couple of guys, including former Bonneville racer, Jim Khougaz, who remembered this car. The owner looked to be in his 50s. It featured a chromed ’39 Ford-style windshield frame, a very unusual modification, and twin side exhausts exiting on the left. I’d love to find that one, wouldn’t you?

“Big Bill” Edwards’ ’40 Standard, an HRM cover car in June 1953, was another standout. This baby packed a 4-71-blown Cadillac. On the street, he ran a four-barrel; at Bonneville, he swapped manifolds for four Stromberg 48s, fitted the requisite belts, and increased the Caddy engine’s output by over 50 percent. HRM reported the car turned over 150 mph in street trim. Try that with your ’40 coupe.

Over the years, I made a list of all the things I’d do to my ’40, when I finally acquired one. My car currently has a 276-cid stroker, and runs an Edelbrock Super Dual and Edelbrock heads, a Motor City Flathead 3/4 cam, and Lucas ignition. The transmission is a three-speed column shift and the rear is a Columbia two-speed. After I scrounged up the parts, Ben MacDonald of Stuarts Draft, Va., installed a nicely restored stock heater, converted the electrics to 12 volts and topped that work off with a Powermaster “Powergen” that resembles an old Ford generator, but is actually an alternator.

Future plans call for my pal Warren Barbie to install a 4-71 — I have a rebuilt one ready to go on the shelf, with a pair of 2100 Holleys. I’ve measured, and it’ll just fit under the hood with two small NOS Badger air cleaners. I fantasize about getting one of Mark Kirby’s new Motor City Flathead 327-cid aluminum blocks, installing a full-race cam and topping it with that blower. The ignition will be an Ollie Morris-modified Harman and Collins HR-101 magneto – I’ve got one of those, too – mounted on an Offenhauser lead plate. I might have to install a beefier gearbox, but maybe not. I’d prefer to retain the old driveline and the column shifter. Can you spell “sleeper?”

Ford’s ’40 coupe is perfect in my eyes. I wouldn’t change one piece of side trim, but thanks to my friend, Jim Walker, I do have a lovely pair of narrow ’41 Studebaker tail lamps. They would fit quite nicely along the curvature of the ’40s rear fenders. The stock chevron taillights are a ’40 signature item, but if you’ve ever seen a ’40 with those slender Studebaker lights, you’ll know why I sometimes think of changing them.

Meanwhile, my Cloudmist Gray ’40 coupe really runs beautifully. The Bill Pupo-rebuilt Columbia shifts quickly and smoothly, and the basso profundo rap from its twin pipes reminds me of sitting in Miss Durgin’s math study class, with open windows, some 50 years ago, listening for the sound of John Knowles’ coupe exiting the parking lot at Swampscott High.

They say you can’t go back, but I know you can.

I’ve owned a lot of very exciting cars – two Ferraris, a Lamborghini, five Morgans and more — but these old Fords still strike a responsive chord that never fails to make me smile. Years ago, I wrote that for a generation of Ford enthusiasts, Henry could have thrown the mold away after he made the ’40.

Nothing’s really changed.

CLICK HERE to tell us what you think in the Old Cars Weekly Forums