Had Ford chosen to squeeze one more year out of its first postwar design, few would have complained. Although the flathead V-8 kept it connected to the past, the 1949 Ford was, in many ways, close to a complete break with the cars that had come before it.

Introduced in 1949, Ford's first postwar design was updated twice by changing details. A new two-door hardtop, the 1951 Custom Deluxe Victoria, freshened the look considerably.

Coil springs up front and parallel leaf springs at rear had sent the transverse leaf springs into oblivion. They were joined by the torque tube that had been dispatched by an open driveshaft. All of that combined to move Ford into the modern world, and it's hard to imagine how anyone could have seen even a distant relationship between a 1949 model and its immediate ancestor.

The 1948 Ford looks exactly like the prewar car that it is, thanks to bulging fenders, general roundness and the slight suggestion of vestigial runningboards. It was the standard formula for quickly restarting production of civilian vehicles, so Ford had plenty of company. But no sellers' market lasts forever, and Ford's solution to that fact was brilliant.

The 1949 design was the essence of slab-sided with its utterly clean shape. A simple horizontal taillight trailed out of each quarter panel to serve as the sole break to an otherwise smooth surface. The front end's spinner grille was the car's least-restrained feature. It was a package done with good taste, and the buying public loved it passionately enough to buy almost 1.2 million examples. With minor details updated for 1950 and the addition of the specially trimmed Crestliner, sales went over 1.2 million.

The Crestliner, a two-door sedan targeting the General Motors hardtops, was pleasant, but it remained a two-door sedan. As such, it drew just under 18,000 orders. It returned for 1951 with less success ' about 8,700 sales ' a fact that might well have had something to do with the introduction of another new model.

For 1952, what had been called the Custom Deluxe Victoria became the Crestline Victoria. The two-door hardtop was as well suited to the new body as it had been to the 1951 model that introduced it.

The Custom Deluxe Victoria was a two-door hardtop every bit as attractive as the competition. It was, Ford boasted, "the car that gives you the smart styling of a convertible with the snugness of a sedan. It's the belle of the boulevard... built especially for those with a yen for distinctive design."

The hardtop was a near-perfect fit to a body that was now in its third year with only mild restyling. The chrome trim around all of the windows, not to mention the rear pillars and the two thin vertical strips that dressed the oversize rear window, created a car much different from a Crestliner or any other Ford two-door sedan. Customers agreed, as this new model made roughly 110,000 sales.

It was a good year for Fords in another way, too, thanks to introduction of the Ford-O-Matic automatic transmission. One of the "43 Look Ahead features," it shared billing with Hydra-Coil springs and Viscous Control shocks, all of which led to the promise that "you can pay more, but you can't buy better than the Ford." Perhaps, but little else was new.

The same straight-six and V-8 were under the hood, and their displacements ' 226 and 239 cubic inches, respectively ' were unchanged since 1941. Their output had been 95 and 100 hp since 1949, and although the two were flatheads, the very fact that Ford offered both placed it ahead of its "Big Three" competition. Among the independents, only Studebaker had a V-8, an overhead-valve unit introduced in 1951, to accompany its flathead six.

Ford stuck with its engine choices for 1952, and that really wasn't a bad decision; they might have represented less-than-cutting-edge technology, but they had no ticking-time-bomb problems. Besides, they were going into an all-new body. The 1952 models were as far from the 1951s as the 1949s had been from the 1948s. Even boxier than their predecessors with a beltline that seemed higher, they nevertheless were unmistakably more modern.

The "big '52 Ford" was the "greatest car ever built in the low-price field," according to the advertising, and if that straightforward claim wasn't enough to close a sale, there were the added facts that "it's the ablest car on the American road" and the "newest car under the sun." The statements about "greatest" and "ablest" are broad enough to withstand nearly any challenge, but the 1952 Fords were not quite the "newest." Aside from their relatives at Lincoln and Mercury, there were also the 1952 Nash and Willys ' the latter raising the problem of being newer than a car in its first year of production ' even if none of that detracts from the actual design.

The previous body had been a slab-sided box so free of unnecessary trim in most models that it approached elegance, and Ford kept much of that simplicity in its new design. High, round taillights flowed out of the tops of the quarter panels, but no longer trailed into the side sheet metal. Instead, the slab sides were relieved only by a curious reminder of the past, a fake fender line stamped into the quarter. A larger one-piece curved windshield looked out over a slightly flatter hood, and the front end reverted to a single spinner as in 1949 and 1950 from the dual spinners of 1951.

The line had no direct replacement for the earlier Crestliner two-door sedan, but the Custom Deluxe Victoria was now the Crestline Victoria, and looked as good as it had one year earlier. Some 77,000 examples were sold, and if that figure didn't place it at the top of Ford's charts, it certainly didn't provide cause for concern.

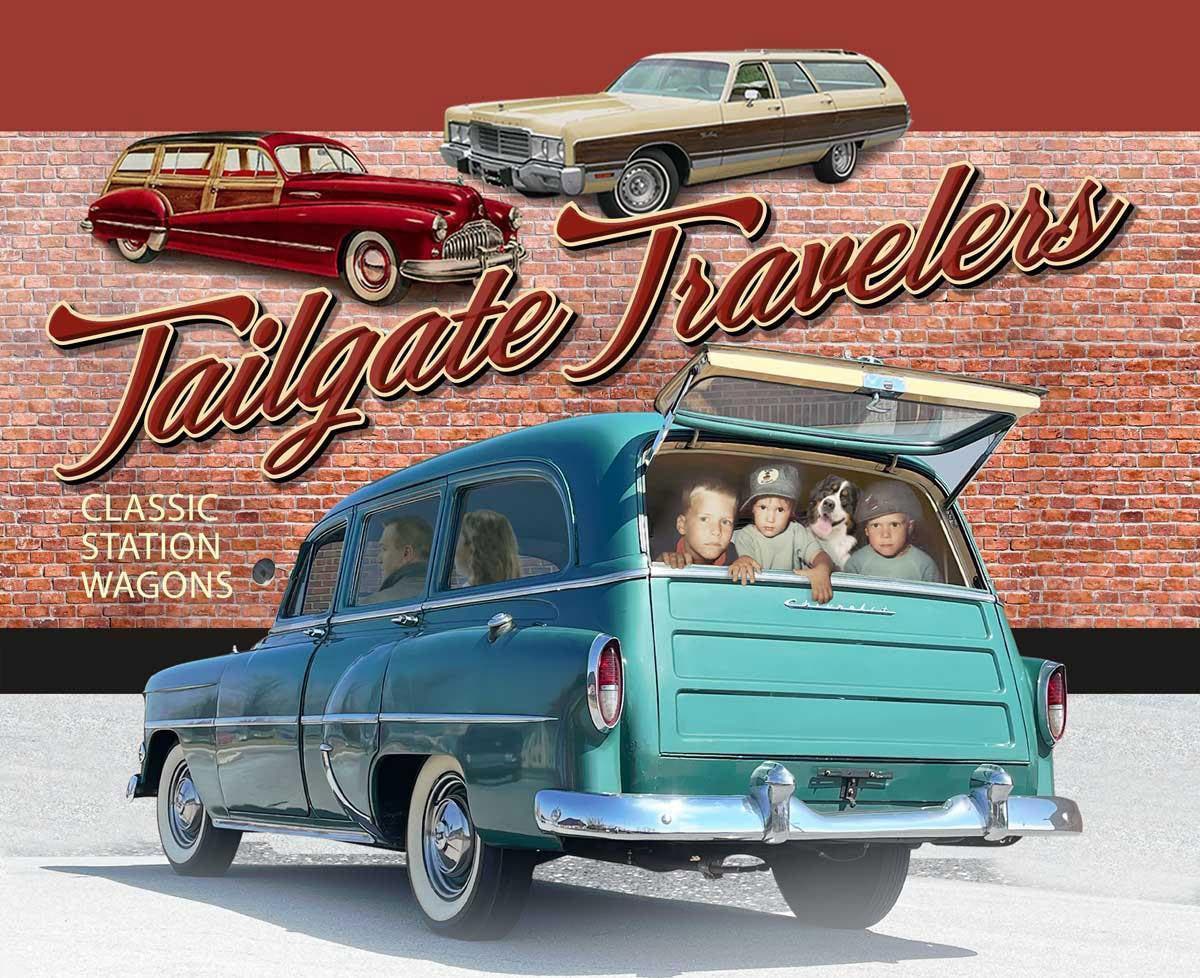

The original Crestliner was not the only model to disappear in the transition to 1952's new style. With it went the wood-bodied station wagon, which every manufacturer was quickly dropping. For all of its character, the woodie simply had too much going against it in everything from maintenance demands to repair costs and couldn't hope to compete with the steel-bodied version in practicality. The 1952 wagon, unlike the two-door woodie it succeeded, offered several trim levels in two- and four-door configurations.

Ford's model range would continue through 1954 with minor facelifts, and in all of that, it was easy to overlook the proof that, even at Ford, flatheads were fading away. Ads spoke of "the newest, most modern Six! It has free-turning overhead valves and it's the only all-new, low-friction, high-compression Six in the industry." Its 215 cubic inches produced 101 hp, up from 95 hp from the earlier 226-cid flathead, but for the faithful, "Ford's high-compression Strato-Star V-8 ' now 110-h.p. ' is the most powerful engine in its field." By 1954, of course, it was gone, and ads emphasized that "... you can have either of Ford's two new high-compression overhead-valve engines ... the 130-h.p. Y-block V-8 or the 115-h.p. I-block Six. Both are as modern as tomorrow with advanced overhead-valve, low-friction design for greater economy..." The six was new in that its displacement was now 223 cubic inches, while the V-8 was a completely new design. It provided the same 239-cid as the flathead had, but its 130 hp easily topped the older engine's 110 figure.

The new engines severed a major tie to the company's past, but just as the Victoria hardtop had appeared late in the previous body's run and carried over into the new 1952 line, a new model arrived in 1954 and would continue into the restyled 1955 cars. It was "... the glamorous new Crestline Skyliner! With new transparent roof panel, the new Ford Skyliner is the top hit of the '54 season..."

In effect, it was a Victoria with a tinted panel above the front seat, and with 13,000 sales, it wasn't really the hit of the season, but it was successful enough to return for 1955 as the Crown Victoria Skyliner. Changing times and dwindling sales, though, made 1956 its final year.