The return of the ”Timbs Special” roadster

Many scratch-built custom creations were fully backyard efforts with fundamental engineering based on production car technology, but Norman Timbs’ car was very different. So was Timbs. He was a skilled mechanical engineer who’d earlier designed the 1947, ’48 and ’49 Indy 500-winning Blue Crown Specials, driven by Bill Holland and Mauri Rose, and worked with the irrepressible Preston Tucker on the Tucker 48 Torpedo design. Timbs’ was an unsual builder, and his amazing “Timbs Special” roadster was a creation was unlike any other.

By Ken Gross

Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear, when custom cars, as we regard them today, hadn’t yet clearly been defined. In the 1940s, there were still coachbuilders such as Bohman & Schwartz (Pasadena, Calif.), Coachcraft (Hollywood, Calif.), Howard “Dutch” Darrin (Santa Monica, Calif.) and Enos Derham (Rosemont, Pa.) who artfully restyled production cars for clientele who could afford to commission a bespoke vehicle.

At the same time, pioneer customizers such as Harry Westergard (Oakland, Calif.), along with Los Angeles-area craftsmen George and Sam Barris, Gil and Al Ayala, Link Paola and others were chopping tops, stripping off chrome, reworking bodies with fadeaway fenders and significantly altering the appearance of what were then relatively late-model cars. They were joined by countless backyard practitioners whose numbers increased exponentially across the United States, especially after cheap, easy-to-use fillers such as Bondo and fiberglass matting became available.

Customizing techniques were promulgated country-wide in Dan Post’s “Blue Book of Custom Cars,” numerous Fawcett one-off publications and, when Robert E. “Pete” Petersen’s magazine empire took flight, Hot Rod, Car Craft, Rod & Custom and even Motor Trend chronicled the burgeoning custom car scene.

There was another category of custom car that pretty much defied description. It includes the works of talented men who basically designed their cars from the ground up, usually (but not always) using a modified proprietary chassis along with engines from production cars. More often than not, they’d build one car for their personal use, and that vehicle, if it were sufficiently striking, might appear in a magazine, along with information — and even a cutaway drawing — detailing how it was conceived and constructed.

Building a cover car

While many of these scratch-built custom creations were fully backyard efforts with fundamental engineering based on production car technology, Norman Timbs’ car was very different. So was Timbs. He was a skilled mechanical engineer who’d earlier designed the 1947, ’48 and ’49 Indy 500-winning Blue Crown Specials, driven by Bill Holland and Mauri Rose, and worked with the irrepressible Preston Tucker on the Tucker 48 Torpedo design. More on Timbs later, but first, let’s talk about his one-of-a-kind car.

The sleek, aluminum-bodied, rear-engine roadster was featured on the cover of the second issue of Motor Trend in October 1949. A lovely model, standing behind the car, posed in the driveway of a then-contemporary ranch house. The Timbs Special’s immense tapered tail extended toward the camera. The car’s lozenge shape represented a stunning contrast to the era’s domestic models.

Notable features included skirted fadeaway fenders; a close-coupled, contoured cockpit without doors; a raked and split windshield; “Siamesed” dual exhaust tailpipes (like those on a Duesenberg Model J); and ’39 Ford teardrop tail lamps. Its 15-inch wheels were shod with wide whitewall tires and accessory hubcaps that resembled Cadillac “sombreros.”

Without benefit of a four-color cover (early MT covers had black-and-white illustrations), readers couldn’t appreciate the Timbs roadster’s deep, almost Titian red-maroon finish, speckled with gold flake, but they surely must have been stopped in their tracks by this car’s futuristic appearance. In the post-World War II era, Volkswagen, Porsche, Tatra, the Renault 4CV and the ill-fated Tucker all espoused rear engines, but that configuration was still comparatively rare.

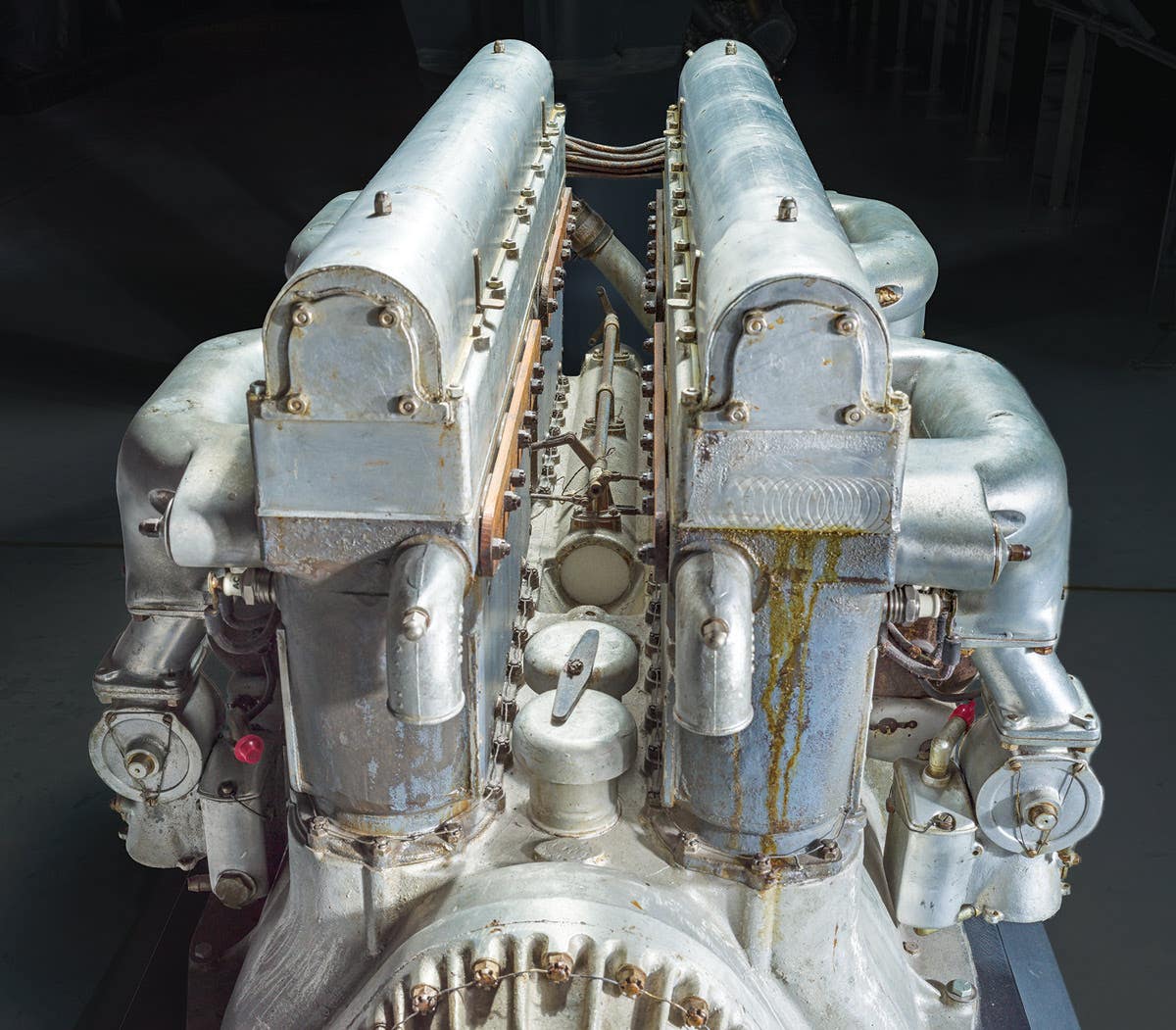

The Timbs roadster’s massive aluminum tail hinged just behind the cockpit and opened hydraulically, with a single ram to reveal, and provide access to, a 1947 Buick straight-eight that was fitted with dual carburetors. Earlier, Buick offered “Compound Carburetion” in 1941 on its top-tier models, and that manifold appears on this engine; Timbs reportedly ordered the powerplant as a “crate motor” from a Los Angeles Buick dealer. A chromed valve cover was added for engine aesthetics. The long straight-eight engine was located nearly in the center of the car’s chassis. A spare wheel and tire was mounted directly behind the engine.

Designed by Timbs, the chassis was a unique design using 4-inch-diameter chome-moly tubing that was capped at the ends and pressurized by a small air compressor, allegedly to help stiffen the frame and supply air for the air horns. The solid front axle was a conventional Ford I-beam. The rear suspension consisted of a Packard center section with modified Ford axle bells, centered by a Timbs-designed independent swing axle that was custom-made for this car.

The snug cockpit, accessible via step plates on each side, looked like that of a high-powered luxury speedboat, with a Stewart-Warner five-gauge accessory panel offset to the right that included a rare 0-to-5,000-rpm tachometer. Other instruments, including an Echlin fuel pressure gauge, were mounted in front of the driver. The full complement included a speedometer, vacuum gauge, air and oil pressure gauges, as well as dials for fuel and water temperature, and an ammeter. There was a wood-rimmed three-spoke accessory wheel and a column-mounted Ford shift lever. As the pièce de résistance, the cockpit, dash surrounds, door panels and seat were resplendent in tan tuck-and-roll leather. No top was ever fitted.

The entire front end of the roadster was a single curvaceous piece, with an ovalesque chromed grille reminiscent of a then-contemporary Cisitalia. It was flanked by a pair of very low-mounted inset headlamps that were in turn framed by a plated nerf bar that echoed the shape of a similar two-plane unit on the rear. The radiator was mounted behind the grille. There was no hood opening, there were no doors. The only visible cut line was the thin vertical break behind the cockpit that separated the extended tail section.

At first glance, as there were no chrome trim accents, the entire car appeared to be molded in one continuous form. An underbelly undoubtedly helped its aerodynamic efficiency. The overall effect was quite startling, and for 1949, when most production models were still relatively tall and boxy, it must have resembled a car from outer space. Reportedly, it was inspired by the ill-fated Auto-Union high-speed record-setter, driven by German driving ace Bernd Rosemeyer before his fatal crash on the Frankfurt-Darmstatt autobahn in 1938.

Using quaint language that was typical of the 1940s, Motor Trend described the Timbs roadster as “an unusually streamlined maroon job.” There was no article on the car per se, but the description — really just a photo caption — stated that the car took three years to construct. It was said to be 17-1/2 feet in length with a 117-inch wheelbase, and it had a 56-inch tread and weighed 2,500 lbs. Oh, and the lovely Miss Ethel Williams was a Rita La Roy model.

Apparently Norman Timbs drove the car, but not a great deal. It appeared at a few shows to great acclaim, but little is known of its in-use history. Timbs, who lived in Van Nuys, Calif., at the time, advertised his “two-seater sports” in Road & Track in February 1950 for $7,500. The R&T classified ad claimed the car was capable of speeds in excess of 100 mph and it had been driven less than 5,000 miles.

The path to oblivion

In 1952, the Timbs Special was owned by an Air Force captain named Jim Davis, who lived in Manhattan Beach. Wayne Thoms wrote a story about the car in the February 1954 issue of Motor Life entitled “Almost Airborne.” In the photographs, the Timbs car appears to have been repainted in a light color. Thoms reported that engine and driveline were 1948 Buick, and noted that the steering column and ignition lock were Ford components. His article stated the height of the car at the windshield was 38 inches and that the hand-formed aluminum body, built in sections on a wooden buck then meticulously welded together — had been built by noted LA-area race car fabricator Emil Diedt at a cost of $8,000.

It’s unclear whether Thoms or the author drove the roadster, but the Motor Life article claimed “...the performance is almost as fantastic as the appearance,” that the Buick engine “...had been hopped up to develop in the region of 200 bhp,” and “...a top speed of 120 mph should be no problem.” Thoms made some interesting comments on the car’s handling:

“Fortunately, this car has the essential ingredients — precise steering, flat cornering, positive brakes — all necessary safety factors which are too important to overlook. Suspension is through conventional transverse leaf springs all around. A De Dion-type rear axle provides independent suspension for the rear wheels, needed because the engine, transmission and differential are in line, virtually as a unit, with no driveshaft separating transmission and rear end. If this is confusing, remember that the engine is in the rear; the only thing in front of the driver and passenger being the radiator which, incidentally, mounts a small electric fan for auxiliary cooling.”

After USAF Captain Davis’ tenure, the ex-Timbs two-seater had a few subsequent owners; it reportedly appeared in a TV episode of “Buck Rogers;” it was displayed for many years in front of the Half Way House restaurant in Saugus, Calif., where children played and jumped on its fragile aluminum body; and it appeared briefly in a few frames of the Nicholas Cage film “Gone in 60 Seconds.” Carelessly stored outdoors by an unknown owner in Antelope Valley, in California’s high desert, it was then bought by a man who apparently was a prop man for a Hollywood studio. The famed Norman Timbs Special deserved a better fate. Thankfully, that was about to happen.

Locating and preserving a legend

I first saw the Timbs Special at the Petersen Museum where it was stored prior to a 2002 Barrett-Jackson auction. Exposed to the elements for years, abandoned and forlorn, it was in very rough shape. Gary Cerveny purchased it at that sale for just $17,200. “I didn’t know about the car until I saw it at the auction,” Cerveny said. “It looked intriguing, and when it didn’t seem to be selling, I decided to bid.”

Cerveny, who likes to drive all of his 35 collector cars, simply wanted the Timbs roadster to be a good driver. But ensuing publicity in Mark Morton’s Hop Up magazine and on the Web convinced him that this was an important car, and it deserved a first-class, historically accurate restoration.

“Some time earlier, I restored a belly tank,” he recalled, “and as most of the Timbs car was all there, I mistakenly thought it’d be an easy restoration.” After performing much of the engine work and beginning the body refurbishing, Cerveny realized, “as the process went along, it was more complicated than I thought, and I was in over my head.” Roger Morrison recommended that Cerveny send the car to Dave Crouse’s shop, Custom Auto, in Loveland, Colo.

Crouse, who has restored several important historic hot rods, said the restoration “...was very difficult. This car was built as a concept exercise,” Crouse continued, “so we had to do a lot of work to make it function properly. The tail section is huge, and a previous owner apparently couldn’t lift it up easily, so he cut a large square hole in the top of the rear section to access the engine. He also cut the wheel wells open to change the rear tires. Workmanship on the body is first rate,” Crouse reported, “but there were no stiffening members to help the body retain its shape.”

“Gary and his dad began the aluminum patching and repairs,” Crouse continued, “but they were dealing with huge compound shapes, and their torch work resulted in some panel warping. Once the car was in our shop, Rex Rogers, my metal guy, carefully restored the panels and then fabricated aircraft-style ribs so the aluminum body could maintain its shape and we could paint it.”

“The aluminum was pretty frail,” added Rogers. “The windshield posts were badly corroded, so we recast those. And the dash had been changed.”

“We had to have a system to lift the body up,” Crouse explained. “So we installed an electric motor screw jack that bolts to the frame in the same place as Timbs’ original (and much too powerful) hydraulic strut. This was a practical step; the heavy body has to open for access to the engine and the rear suspension.” The only other substantive change was converting the electrical system from six to twelve volts.

“This car is a monster to work on,” Crouse added. “The nose is fixed; there’s no hood and the radiator is in front, with an expansion tank located behind the cockpit bulkhead. We got all the mechanicals perfected, but it took time. Most of the linkages and controls are aircraft bell cranks. A few of them were missing and some didn’t work very well. There’s a ’46 Ford steering column with a column shift and it goes to the nose of the car. The linkage has to run all the way to the rear and operate smoothly.

“One problem was the Buick transmission,” Crouse said. “Unlike a Ford, with two levers on one side, the Buick has one lever than goes fore and aft and another that goes in and out. Fabricating functional shift, throttle and clutch linkages took some re-engineering. We actually drove the completed chassis around quite a bit to ensure everything worked before we mounted the body on it.

“There were no splash shields behind the wheels to keep water from coming in, so we fabricated those,” he said. “The full belly pans were missing, so we made those, too. Our intent was to build a show car, but make it usable and drivable.

“The original workmanship is incredible,” Crouse enthused. “The De Dion-type independent rear suspension uses Packard U-joints on a Ford banjo with Ford axle bells, anchored by a conventional transverse leaf spring and tubular shock absorbers. But the geometry apparently wasn’t right, so to make it work, someone kept adding more springs. We installed the regular Ford semi-elliptic spring pack and used air shocks powered by the car’s compressor. It works beautifully now.”

Crouse believes Timbs’ intent to stiffen the chassis by pumping air into the tubular frame under pressure was never practical.

“You’d need 1,000 psi or more before you’d notice much change,” he said. “That said, Norman Timbs was way ahead of his time. He was on the inside of the Los Angeles racing fraternity, working with the best race car fabricators, and it shows. They built this car for him. The welds and the machine work on this car are gorgeous. Whoever did the body knew what he was doing. Although there’s no proof, it could very well have been Emil Diedt.

“This restoration wasn’t something we just whipped out,” Crouse explained. “After we finally had the shape corrected, the surface preparation took forever. To obtain a straight, even parting line, we had the tail section on and off. It’s so big you can’t reach across it, so we stood it on one end and built a scaffold to work on it. It’s the weirdest thing we ever had to do, but sometimes you’ve got to get creative.

“My painter outdid himself,” Crouse said. “We had a little chip of the paint from a go-kart that Timbs had built for his son, Norman Jr. After consulting with a few people, Gary Cerveny took it to Stan Betz, who experimented with several shades, and then expertly mixed the correct color with the right gold flakes. We painstakingly sprayed it on in several steps, from base, to color, to the clear finish. It was like painting a 747, because the car is so huge.

“Although most of the parts were there, we had to locate some of the rarer pieces,” Crouse said. “Because we had photographs of the instruments, we couldn’t substitute; we had to find the right ones. There’s a small pressure gauge on the left and we used a magnifying glass to identify it. It wasn’t Stewart-Warner — it had a crimped bezel — and we were stymied for three years. Pat Swanson, an instrument expert from the Pacific Northwest, told us it was an Echlin 0-10-PSI mechanical fuel pressure gauge. Even better, he had one, and he gave it to us to restore. The hubcaps are Lyons accessory items, and it took years before we found a pair to restore.”

A custom comes home

Dave Crouse said he’d known about the Timbs Special for a long time.

“The guy I use to bird dog cars and parts for me said there was ‘...a streamliner in the high desert.’ When he described it, I told him to buy it for me. But somehow he didn’t; the car was used as a movie prop, and the owner at the time thought he’d get a lot of money for it when it came up for auction and Gary bought it. But eventually, it came home to Poppa, and we got to restore it.”

Crouse, who drove the car in test shakedowns without the aluminum body, as well as after the shell was permanently installed, said, “It’s quite nimble for its size and it really feels secure on the road. It’s a little like driving a bus,” he quips, “because you’re sitting so far up front with that long tail behind you.”

Cerveny, who disassembled and rebuilt the engine, said that two cylinders had water in them. He wanted to keep the original block, so he installed a pair of cylinder sleeves, followed by a complete rebuild. Cerveny notes that the crosshatches from the factory cylinder bore honing were still visible, indicating that the engine had been run very little. Modifications include the aforementioned twin carburetors. A pair of factory cast-iron split exhaust headers empty into twin Smithy’s mufflers, resulting in a satisfying rumble from the parallel tailpipes.

Three years later, after a great deal more money was spent, the gleaming, beautifully restored Norman Timbs Special is complete.

“You don’t find a car like this very often,” Crouse said, obviously pleased with his shop’s work. “We’ll tackle anything. But I can’t credit Gary enough. Whenever there was a crunch, he stepped up and we went for quality.”

“I’m really excited about this car,” Cerveny added. “I like European art-deco designs, and now that the car is completed, I’m even more interested in it, and I have no plans to sell it. My wife Diane is unbelievably excited about it, too. It’s going to be the centerpiece of our collection.”

Rescued from the high desert, restored to a “fare thee well,” primed for its first public appearance in decades at the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance on March 14, the long-lost Norman Timbs Special is certain to dazzle the crowds.

For more information on the Amelia Island Concours d’Elegance, go to www.ameliaconcours.org or call 904-636-0027.

MORE RESOURCES FOR CAR COLLECTORS FROM OLDCARSWEEKLY.COM